Meet the Venice velvet weavers, whose clients include Mariah Carey and the Vatican

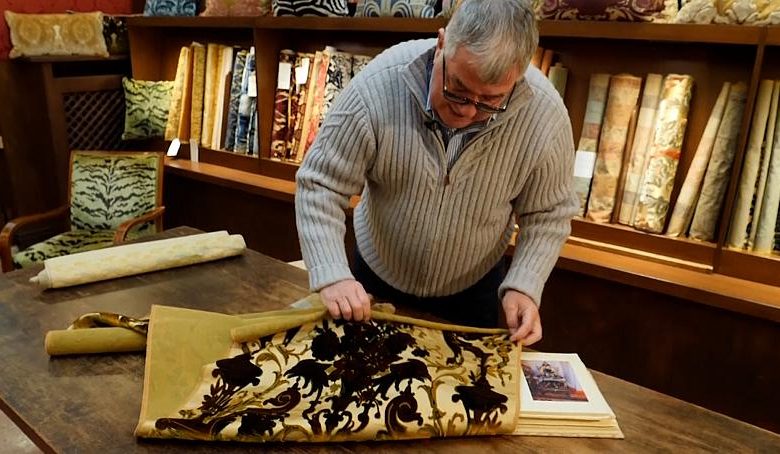

CEO of Tessitura Luigi, Alberto Bevilacqua showcases a velvet cloth

The origins of the textile tradition

“(Velvet weaving) was one of the most important economic activities (in Venice) and people came to Venice from all over the world to buy velvets. Then, obviously, there was a decline in this production, but it was important to preserve this excellence because if knowledge is not passed on, it is lost, and a very important artistic and cultural heritage is lost,” says CEO of Tessitura Bevilacqua, Alberto Bevilacqua.

Venice is famed not only for its architects, sculptors, painters and writers, but also for its textile artisans, who in the past produced fabrics that are inimitable for quality and refinement.

Between the 13th and 18th centuries the velvet produced in the lagoon was used to make the most luxurious clothes for European nobility.

Production of velvet, alongside silk, began in Venice thanks to some 300 artisans (weavers, spinners, and dyers) who fled the Tuscan city of Lucca for political reasons.

By the 16th century, the precious fabrics produced in Venice had become the most important source of wealth for the city of canals.

But the galloping industrialisation of the 19th century quickly erased centuries of tradition. It was not until towards the end of the century that Europeans started recovering the know-how of the ancient decorative arts, including weaving.

Keeping the craft alive

In 1875, Luigi Bevilacqua dusted off the old looms. Six generations later, his company continues to jealously safeguard the secrets of this ancient craft.

It is by no means a simple art form, requiring a lot of time, patience and physical effort.

“To prepare a loom for weaving takes several months, sometimes even a year. For example, when we made this fabric for the Kremlin, we worked for a year before we did it,” explains Bevilacqua.

When the Russian government commissioned them to make this fabric to upholster some chairs in the Kremlin, the Bevilacqua weaving mill didn’t know if it would make it.

The pattern was a French design from nearly 300 years ago, but the loom used to produce it had been out of action for 50 years.

So the weaving technicians had to modify one of the looms, and it took six months just to set up the machine, punch cards and thread spools.

The weaving itself was also particularly complex, because it was the only case in which two weavers worked on the same loom at the same time.

Normally, only one weaver works on each fabric, setting the loom according to their strength, the length of their arm and the tension they need for the threads.

A modern day innovation to the traditional wooden loom

The looms may date back to the 18th century, but they work today thanks to an 19th-century invention.

It’s a machine that, like an ancestor of the modern computer, reads the punched cards, noting the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions in a sort of secret code that the loom uses as a map to make a design.

Manual weaving, however, requires a series of complex operations that increase production times.

First the punched cards are prepared, and thousands of them are needed because each one represents half a millimetre of the design, which is sometimes as much as 1.5 metres long.

Then there are about 15 threads of silk that must be attached to the loom. No more than 20 cm can be woven each day for the most precious and complicated velvets.

But it is precisely the complexity of the work behind each fabric and the final result of the finest workmanship that has meant that for the last 70 years requests have continued to come in from all over the world.

The luxury status of handwoven Venetian velvet

In addition to the Kremlin in Moscow, the White House in Washington, orders come in from celebrities and royal palaces around the world, the Vatican, the Quirinale (home of the Italian president) and high end fashion houses.

A piece of tiger velvet crafted by Tessitura Bevilacqua was used to upholster chairs in singer Mariah Carey’s mansion.

Giulia Incipini has been working at Tessitura Bevilacqua for seven years.

“This is physical work, so the construction and preparation of the loom as well as the weaving are all done by hand, all physical and all done by us,” she says.

Not everything she works on can be shown off: she makes sure to keep out of view a velvet they have been weaving in recent weeks for a famous Italian fashion house, a design that is still “top secret”.

Incipini spends hours weaving in the workshop using her whole body as if she were a master puppeteer.

Preserving such an ancient tradition can mean sweat and frustration, particularly when the machine jams, or you get lost in the labyrinth of thousands of threads.